Royal Commissioner John Dyson Heydon’s damage to his own inquiry should remind Australians that their cultural warrior Prime Minister loves nothing better than a good show trial. That’s when a government uses a legal forum to expose its political enemies to cross-examination, stereotyping, ridicule and, all going well, banishment.

Always on the look-out to hit back with his perception of the enemy’s techniques, the habitually divisive Tony Abbott established a high-profile inquiry into the fatally shoddy installation of roofing insulation, which he might associate with the relatively environment-friendly Rudd Labor government.

And he established a webcasting, headline-seeking trade union inquiry, whose commissioner, Dyson Heydon, has now smugly been advertised as speaker at a Liberal fundraising dinner, thus publicly confirming his exemplary right-wing credentials. He was already known as almost a parody of a conservative High Court justice and as a writer for Quadrant, a small magazine that to this day jokingly suggests it never benefited from early CIA funding, while conceding that receiving such largesse would have been “hardly shameful”. Even a basic understanding of legal processes must recognise the need for at least a pretence of objectivity.

Tony Abbott appears to have learned the political value of show trials, if not from the twentieth-century greats, then at least twenty years ago as a backbencher close to John Howard. As the then Opposition leader, Howard arm-twisted two friendly State governments into holding Labor-punishing royal commissions that picked off an uppity woman and Indigenous activists, respectively. The two inquiries in 1995 eased his way to the Prime Ministership soon after.

Carmen Lawrence had moved into Federal Cabinet, and was mooted as a potential Labor leader. So, Howard persuaded the West Australian government to hold a public inquiry into some obscure instance of alleged political expediency. It had something to do with her possibly misleading Parliament about a confidential Cabinet discussion while she was still that State’s Premier.

I used to work (and still often do) to the soundtrack of Classic-FM, so that after four months of reports from that inquiry, I wrote to the managers of ABC News complaining that nearly every radio news broadcast, several times daily, included: “Penny Easton committed suicide four days after the tabling of the petition.” Day after day, I heard the mantra, “Four days later Penny Easton suicided.” What, I inquired of ABC News, was the relevance? Was Carmen Lawrence accused of killing Ms Easton? Why was this not cheap innuendo?

Prime Minister Paul Keating called Premier Court’s inquiry a “kangaroo court”. In a moment of exasperation, Commissioner Kenneth Marks himself complained that he couldn’t see the point. Stuart Littlemore’s Media Watch showed a commercial television reporter browbeating Penny Easton as she stood, head in hand, beside her car in a presumably private garage, just hours before her death. Perhaps that warranted an inquiry? But that wasn’t the point – Carmen Lawrence’s career had been severely damaged, and the Keating government with it.

The dirt has stuck. This very day, defending Heydon’s appointment, News Ltd’s Piers Akerman recalled “an inquiry regarding the suicide of Penny Easton 20 years ago”, an untruth helped by the ABC’s seemingly incessant repetitions. Ironically, today’s column also repeated the charge that the ABC, along now with Fairfax, was “a sheltered workshop where Leftist groupthink prevails”. Not my impression.

Especially with the inquiry being in far-off WA, Howard could seem to keep his hands clean, and the journalism was provincial, without the strength and diversity of investigative reporting now available. Howard got away with it similarly in his other inquiry in South Australia.

Those were the days when Howard called racism “racial resentment”, which he assured Australians that he “understood”. This divisiveness could be joined by incessant anti-Labor publicity by pressuring SA’s new Liberal government into holding a public inquiry into Aboriginal objections to building a bridge to a failing marina on Hindmarsh Island. I know this show trial well, because my wife and I wrote about the tussles in a book that publishers wouldn’t touch. This was entirely understandable, given the seemingly unlimited funds being used to attack “secret women’s business”, and silence any opposition. Put it this way, mining companies had much to lose, nationally, from Indigenous claims. Admittedly, the women’s supporters were more inclined to point out that Westpac stood to lose heavily if the marina developers didn’t get their bridge.

Hindmarsh Island was a fascinating story (and, despite no book, Marion Maddox has published more than one academic paper). Among fun and games, the political parties swapped sides. The incoming Liberal government’s Minister for Transport had long led opposition to the Bannon government’s bridge, and had encouraged Indigenous objections; hers was among the Adelaide business families with quiet get-aways on the island. But the Liberals quickly decided to replace the ferry with a bridge as part, it seemed, of a wider campaign to destroy Labor’s Robert Tickner and undermine Mabo Native Title legislation. Incidentally, the same SA minister’s family were big suppliers of concrete, used in transport infrastructure and mining developments.

Among research amusements, I recall ringing a top Adelaide barrister to ask why he had briefed solicitors on the inquiry (it’s usually the other way around), until he expostulated: “I’m not going to be cross-examined like this.” A bit rich from a QC, and I was only trying to confirm whether it was Howard himself who had organised the barrister’s central role. Or perhaps it was through Ian McLachlan, who was dropped from the Opposition front bench for a misleading statement about how he came by, and distributed, the women’s account, marked “Confidential”, and mistakenly delivered to his office.

Or it might have been Tony Abbott, who was Howard’s right-hand on this one, and working with a small cabal in Adelaide, where he used to fly many weekends, staying with Adelaide Review editor Christopher Pearson at his get-away at Delamere, south of Adelaide. A strong writer and editor, Pearson had swung through his life from choir boy to far Leftist to conservative Catholic who required Mass daily, and in Latin.

Or it might have been Tony Abbott, who was Howard’s right-hand on this one, and working with a small cabal in Adelaide, where he used to fly many weekends, staying with Adelaide Review editor Christopher Pearson at his get-away at Delamere, south of Adelaide. A strong writer and editor, Pearson had swung through his life from choir boy to far Leftist to conservative Catholic who required Mass daily, and in Latin.

Post-conversion, Pearson remained openly gay and, while renouncing sexual relations, was famously sybaritic. As a relatively influential Adelaide editor, when he had summoned Abbott, who had been running the monarchist campaign, to meet for the first time, it was over lunch at an Italian restaurant in Leigh St. As the present Prime Minister reported:

We dined at Rigoni’s, an institution where Christopher appeared to be a permanent fixture, his table expanding or contracting according to the number of his acquaintances who happened to be passing by. For Christopher lunch was both an art and a science. Arguments could erupt over the correct method of cooking a bechamel sauce or the proper way to roast a duck. In life, he once wrote, “only fools fail to take their pleasures seriously.”

Dinner guests were beginning to arrive by the time we ventured unsteadily into the winter gloom of Leigh Street. Apparently I had passed my audition …

For ten years, Tony Abbott wrote a column for Pearson’s Review, just as Pearson would later help with media releases and edit books for Abbott, turn out speeches for Alexander Downer and John Howard, and contribute columns to the Australian.

As Abbott also recorded last year:

It was an unusual coupling in many ways—“arty versus hearty”, someone had warned him before our first meeting. Christopher was the aesthete; I was the athlete; he was a reformed Maoist and I was a lifelong conservative. Yet he had made it his mission to take me under his wing. Books and CDs started to arrive from Adelaide. If I was to write successfully for the Review, I needed to expand my knowledge and deepen my appreciation of the finer things of life …

Intimacy was Christopher’s natural and permanent disposition … He had no compunction about calling in the middle of a fraught week in Canberra to discuss a conversation with a doctor, an encounter with a taxi driver, or the status of white anchovies on the gastronomic table … Never having children of his own, he revelled in the role of the adoptive uncle.

The Hindmarsh Island show trial was hung on a Channel 10 report by Chris Kenny, who became another pet columnist of Pearson’s, and who also went on to work for senior Liberals in Canberra, and now as a News Ltd columnist, where he has been a bitter opponent of the ABC (his employment on Adelaide’s 7:30 Report had been short-lived).

Pearson and Abbott had ganged up to get the “political correct”, and the big break came with Kenny’s claim that Aboriginal man Doug Milera admitted that the “secret women’s business” had been fabricated.

The most astounding piece of evidence at the inquiry was the playing of Kenny’s full interview with Milera. Not surprisingly, Channel 10 refused the tapes being aired outside the commission. Likewise, Milera’s solicitors told the inquiry that, contrary to Kenny’s original report, Milera actually supported the women, and that he had been on a bender during the interview.

The full interview confirms that Milera was, indeed, so inebriated, and getting more so, as to be almost incoherent. Kenny extracted the widest possible range of claims – starting from the women’s business not being fabricated at all, to Milera having done the fabrication himself. The interview took some long period to tape, with Kenny stopping the camera with Milera needing another drink.

According to the Advertiser, the “controversial television interview with intoxicated Ngarrindjeri man Douglas Milera” was eventually found by commissioner Iris Stevens to be “fair”. Who would doubt a royal commissioner? I can only conclude that we took notes about some other tape at the State Archives. I might also observe that the show trial’s findings subsequently failed in other courts, as happened with those re Carmen Lawrence.

Presumably, Australian judges have some appreciation of the standards expected in a show trial, so that in the tradition of Hitler, Stalin, Mao and the occasional great leader closer to our times, I promise that, once running this country, I’m establishing a raft of commissions of inquiry.

They will examine such matters as:

- Mining company involvement in Australian politics

- The funding of the Institute of Public Affairs, Centre for Independent Studies and Quadrant

- McDonald’s impact on town planning

- Red Bull marketing

- Sugar

- And the outrageous political use of commissions of inquiry.

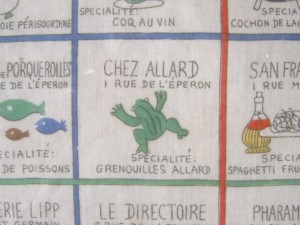

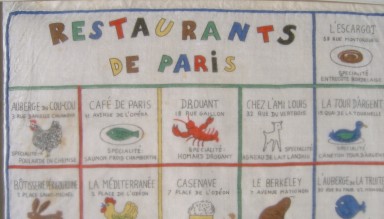

![491720065_a873ca0190[1]](https://mealsmatter.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/491720065_a873ca01901.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![491693630_5b41aa8303[1]](https://mealsmatter.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/491693630_5b41aa83031.jpg?w=300&h=225)

![250px-Peace_sign.svg[1]](https://mealsmatter.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/250px-peace_sign-svg1.png?w=177&h=177)

![JohnLennonpeace[1]](https://mealsmatter.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/johnlennonpeace1.jpg?w=281&h=300)

live comfortably in a restaurant black hole. Sydney critics and columnists frequently rave about places in inner-city Surry Hills, the CBD, Bondi beach and the Lower North Shore. Although we’re still in the Inner West, they rarely come near us. The hipsters have not reached out this far. More tellingly, we live in a weird gap between maps in the Sydney Morning Herald’s Good Food Guide.

live comfortably in a restaurant black hole. Sydney critics and columnists frequently rave about places in inner-city Surry Hills, the CBD, Bondi beach and the Lower North Shore. Although we’re still in the Inner West, they rarely come near us. The hipsters have not reached out this far. More tellingly, we live in a weird gap between maps in the Sydney Morning Herald’s Good Food Guide.

Admittedly only been once, and I had some criticisms (about the need to make the space feel slightly warmer, and not relying on just one glass of champagne to last through all those fabulous introductory snippets), but surely Orana should have been placed much nearer the very top.

Admittedly only been once, and I had some criticisms (about the need to make the space feel slightly warmer, and not relying on just one glass of champagne to last through all those fabulous introductory snippets), but surely Orana should have been placed much nearer the very top.

We’ve just had Anzac Day, which

We’ve just had Anzac Day, which

Apparently

Apparently