EMPTY SUPERMARKET shelves. Flights banned. Cruise lines taking a holiday . . . That’ll pass.

But Parisian bars, cafes and restaurants totally closed? That’s the end of some world or another.

More than just locked restaurants across the globe, urban life closes down and, with it, many seeming certainties. How unconvivial could this get?

My new book, Meals Matter, develops a “radical economics” from John Locke, Brillat-Savarin and others. As the first copies are being printed, a major rethink feels even more necessary. As First Dog on the Moon says: “Things are crazy and scary and they were already crazy and scary before.”

Meals Matter laments the two-century dismissal of meals – the disparagement of domesticity, the corruption of the lively marketplace, and the denigration of the wider, political meal. For this last, I reclaim the name, “banquet”. Needless to say, going along with money’s demands, governments so abandoned their meal – the banquet – that it remains scarcely visible.

Along comes the coronavirus, and governments act financially. Save the stockmarket! This is meant to “save jobs” to maintain metaphorical “bread”, although cynics also know that businesses seek to “capitalise the gains and socialise the losses”.

The government “banquet” should be not just emergency provisioning, but a whole meal. After all, any good meal comprises not just nutrients, but also comfort, pleasure, companionship, beauty, health, learning….

The aristocratic and religious hierarchies embellished their banquets with fine architecture and arts, and employed musicians, dancers, clowns, and jesters to tell truths. They staged whole after-dinner operas.

After pulling down monarchies and theocracies, the people anticipated their own mighty, popular banquets. But capitalism rose up within and against democratic republics, preferring only one meal, that of the market, and that merely conceived as prices.

Without government employment, artists were expected to rely on the market, and private patronage.

Suddenly, performers are out of work. I can no longer attend Verdi’s Attila at the Opera House tonight, nor the Bowral music festival next weekend. With a pandemic shaking live music and theatre to the core, government support looks slim indeed.

New York Times columnist, Michelle Goldberg, just wrote:

it’s chilling to witness an entire way of life coming to a sudden horrible halt. So many of the pleasures and consolations that make dwelling in cramped quarters worth it, for those privileged enough to choose city life, have disappeared. Even if they all come back, we’ll always know they’re not permanent.

Things are changing. Social-distancing and self-isolation atomise face-to-face meals. Yet mass banquets reappear on balconies. Neighbours drop food off at front doors. The whole world comes together as never before.

Just maybe those who survive the pandemic might have been reminded the hard way that meals matter far more than money. If dictatorships haven’t further edged out liberal democracies, the banqueters might appreciate that the political household depends on cooperative health care, decent educations, the performing arts….

You never know, perhaps even mainstream economists will soon disown their slogan, “greed is good.” Governments might re-nationalise airlines….

Michelle Goldberg also wrote: “Maybe when this ends, people will pour into the restaurants and bars like a war’s been won, and cities will flourish as people rush to rebuild their ruined social architecture.”

To help prepare, put in your orders for Meals Matter: A Radical Economics through Gastronomy.

Paris secrets, or at least the dining we’ve enjoyed these past five weeks, with the added test of wanting to return.

Paris secrets, or at least the dining we’ve enjoyed these past five weeks, with the added test of wanting to return.

Nearly 40 years ago, I dined Chez Allard, a then one-star bistro founded in 1932. Monsieur Allard (by then, the son, André) recommended sharing the frogs’ legs, because they were the real burgundian ones, and recommended against their famous specialty of duck and olives, because duck and turnips were briefly in season. Just accept our carafe red, he reassured. I probably had profiteroles. And the meal in a then near-empty bistro was magnificent, the duck among the best things I’ve ever eaten.

Nearly 40 years ago, I dined Chez Allard, a then one-star bistro founded in 1932. Monsieur Allard (by then, the son, André) recommended sharing the frogs’ legs, because they were the real burgundian ones, and recommended against their famous specialty of duck and olives, because duck and turnips were briefly in season. Just accept our carafe red, he reassured. I probably had profiteroles. And the meal in a then near-empty bistro was magnificent, the duck among the best things I’ve ever eaten.

To engage in some national stereotyping, Italians are “exuberant and spontaneous”, Americans are “enthusiastic and demanding”, and Japanese are “delicate and discreet”.

To engage in some national stereotyping, Italians are “exuberant and spontaneous”, Americans are “enthusiastic and demanding”, and Japanese are “delicate and discreet”. My temerity in telling someone the other night about being a “new friend” occasioned further pondering.

My temerity in telling someone the other night about being a “new friend” occasioned further pondering. A couple of older women work on laptops, and one is now on a mobile – she has a friend, or maybe it’s work. A young tourist couple come in for double consumption – photographing their breakfast, before touching it. Are these zillion photos as expendable as Zuckerberg’s 75 million followers?

A couple of older women work on laptops, and one is now on a mobile – she has a friend, or maybe it’s work. A young tourist couple come in for double consumption – photographing their breakfast, before touching it. Are these zillion photos as expendable as Zuckerberg’s 75 million followers? As a restaurateur, I cannot deny having loved our regulars. We had a couple who came fortnightly, for years. They drove quite a distance from a beach suburb, and plainly enjoyed each other’s company. We kept Table 8 for them.

As a restaurateur, I cannot deny having loved our regulars. We had a couple who came fortnightly, for years. They drove quite a distance from a beach suburb, and plainly enjoyed each other’s company. We kept Table 8 for them. PARIS IS ONE WORD worth more than a thousand pictures.

PARIS IS ONE WORD worth more than a thousand pictures.

SOMETHING WAS revealed about my choice of restaurants, or my friend’s, the other day, when he said he was unfamiliar with “natural wines”.

SOMETHING WAS revealed about my choice of restaurants, or my friend’s, the other day, when he said he was unfamiliar with “natural wines”.

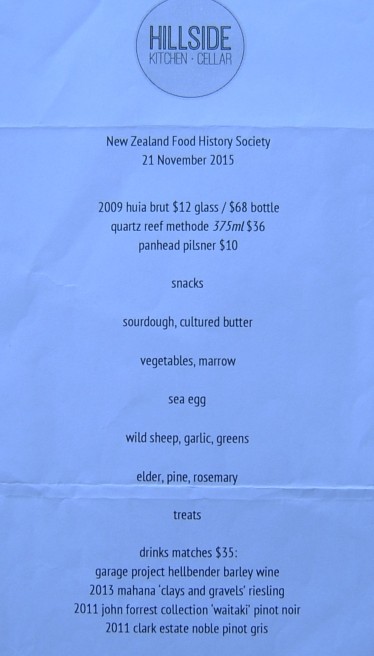

The Kiwi aesthetic is so ever-present that locals hardly notice. The numerous elements go beyond the prevalent black, reflecting the dark beaches and rocky outcrops, and the old-fashioned textures of wool and wood, and, importantly, permit flashes of brightness.

The Kiwi aesthetic is so ever-present that locals hardly notice. The numerous elements go beyond the prevalent black, reflecting the dark beaches and rocky outcrops, and the old-fashioned textures of wool and wood, and, importantly, permit flashes of brightness. The drabness is comforting, and makes a backdrop for subtlety, along with drollery. Think farmer Fred Dagg (comedian John Clark), who in the 1970s always responded to a knock, “That’ll be the door.” More recently, the Flight of the Conchords took a similarly glum gleam into the wider world.

The drabness is comforting, and makes a backdrop for subtlety, along with drollery. Think farmer Fred Dagg (comedian John Clark), who in the 1970s always responded to a knock, “That’ll be the door.” More recently, the Flight of the Conchords took a similarly glum gleam into the wider world.