Capitalism has abandoned neoliberalism and gone disruptive

FOLLOWING perestroika and glasnost and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, capitalism’s boosters trumpeted “liberty” worldwide. Demanding liberation for all, a new Pax Americana would make everywhere safe for corporations.

Under big money’s global message of freedom, such left-liberal political leaders as David Lange, Paul Keating, Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, Helen Clark, Kevin Rudd and Barack Obama pushed progressive cultural reforms with particular support for racial, women’s, gay and other rights.

The trap was that the “rights revolution” in such areas as feminism and multiculturalism provided cover for the corporate capture of government. Under the banner of neoliberalism, the same leaders pushed through deregulation, fiscal “rectitude”, lower corporate taxes, “flexible” job markets, outsourcing, lower trade “barriers”, individual responsibility, etc.

In the flurry of freedom, cultural liberation was outmatched by the bolstering of corporate power.

With governments now firmly in its grip, capitalism moved from neoliberalism to “disruption”. Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg instructed: “Move fast and break things”. Powerful corporate leaders from Zuckerberg, Musk and down asserted their sacred right to do what they wanted – AI, rockets to Mars, armaments, opioids, drill, baby, drill…

Writing about the “disruption machine” in the New Yorker in 2014, Jill Lepore observed that innovation had become “the idea of progress stripped of the aspirations of the Enlightenment, scrubbed clean of the horrors of the twentieth century, and relieved of its critics”.

Long-time Silicon Valley reporter Kara Swisher (Washington Post, 15/02/24) had “watched founders transform from young, idealistic strivers in a scrappy upstart industry into leaders of some of America’s largest and most influential businesses.” With few exceptions, “the richer and more powerful people grew, the more compromised they became.”

Upon Trump’s election as President, digital CEOs rushed for an audience, Swisher reported:

“There was a heap of money at stake, and they wanted to avoid a lot of damage the incoming Trump administration could do to the tech sector. … they also wanted contracts with the new government, especially the military. … More than anything, they wanted to be shielded from regulation, which they had neatly and completely avoided.”

The “invisible hand” of money unleashed disruption (and corruption), and broke pay parity, democracy and civility (not forgetting nature). Along with that, fewer and fewer billionaires supported left-liberal causes, preferring to boost their own fortunes by backing think-tanks and increasingly authoritarian ideologies.

Right-wing populists blamed the “politically correct”, the “woke”, university-educated “elites”, and mysterious liberals who controlled the “deep state”. Raising the “cloud of confusion”, Murdoch opinion-leaders baited their opponents until seeming actually to believe environmental degradation was an esoteric belief, and supporting women of colour impoverished white men.

Historian Ellen Schrecker has charted how the unprecedented invigoration of American universities during the Sixties eventually rebounded, when the right both attacked universities’ “liberalism” and corporatised them (in her studies of universities’ Lost Promise (2021) and Lost Soul (2010)).

Those endeavouring to save the welfare state, worker rights, universities, democracy and the environment have been tempted to display militancy. Israel’s brutality has now prompted campus protests in the Sixties manner.

Caution is warranted, nonetheless. Given how abusive politics suits aspiring demagogues, supporters of left/progressive/Green politics should prefer exposing the sin of over-commitment over indulging in it. Rather than shout back, the liberal left could usefully resort to honesty and openness, and appreciate complexity.

Arguing the benefits of civilised society also means understanding politics more deeply than as just warfare (“class struggle” already proved insufficient).

Contesting the authoritarian appeal of “the strong always win” means re-discovering lost principles. Countering disruption requires a return to something more like Enlightenment political philosophy, seized and shattered by capitalism.

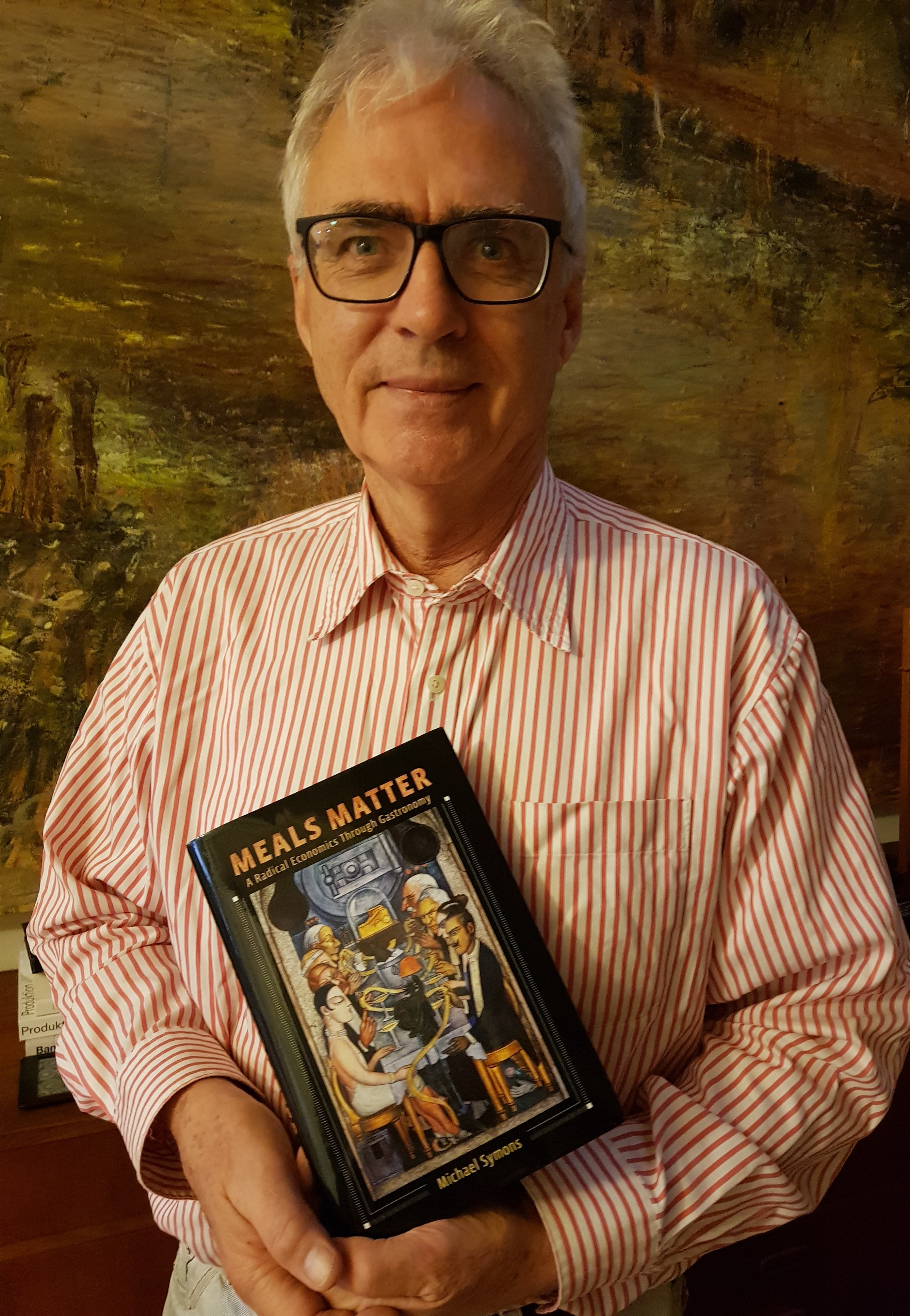

The pre-capitalist basis of radicalism is described in Meals Matter: A radical economics through gastronomy (Columbia UP, 2020). The book also shows how money’s polemicists borrowed selectively from liberal-democratic arguments, and trampled on them.

Grassroots change comes from care and conversation at and about meals (at their different levels)

Australian Blak activist Natalie Cromb has just advocated, with “violence all around us”, for “reimagining our communities to be as they should be – caring, nurturing, healthy, happy and with enough”.

PURCHASE MEALS MATTER THROUGH YOUR favourite seller, several mail-order firms, or through Columbia University Press with a discount.*** E-books are instant.

PURCHASE MEALS MATTER THROUGH YOUR favourite seller, several mail-order firms, or through Columbia University Press with a discount.*** E-books are instant.