“TO THINK I reached the age of 30 without knowing this.” I was considerably older than that incredulous online author when I learned about “aphantasia”, just a few days ago.

Aphantasia is the experience of “reduced or absent voluntary imagery”, that is, we aphantasics are not bothered by a “mind’s eye”, nor its equivalents for the other senses.

We are amazed to learn that, when “counting sheep”, many people actually watch imaginary sheep!

It’s a surprisingly late discovery for us aphantasics, and also for science. Psychologists wrote about it more than a century ago, including Fechner (1860), Galton (1880), Bentley (1899) and John Watson (1913). But then the topic disappeared.

Watson himself might have to take some blame by launching behaviourism’s avoidance of subjective experience in favour of external psychological observation, which would be ironic given how he was a non-imaginer.

This last is suggested by Bill Faw (2009), who arguably led the return to studies of “non-imagers”, the name he prefers for himself and others. In 2015, a neurologist came up with the seemingly catchier, “aphantasia”. Under whatever the name, the research remains rudimentary, especially in relation to the phenomenon’s fascination. For instance, published estimates of the proportion of aphantasics in the population range from 0.7% to 2 – 5%.

Many have discovered the condition when a therapist asks them to visualise. They remain puzzled when asked to, perhaps, put an intrusive thought on a floating leaf and watch it drift away. We recognise the condition immediately it’s described.

If I am asked: “Imagine the sun rising,” I get a glimpse, vanishing instantly, like keying in a password. An imagined apple might have some details, and at least seem red, but then I’ve seen standard depictions of apples since learning “A is for Apple”.

Given imagery’s presumed role in memory, non-imagers generally don’t have such strong recall of even recent events, people’s faces or the narrative of their own lives.

Recent research also shows, for example, that we non-imagers might draw a simpler version of a room from memory, but often with more spatial accuracy. Spatial memory follows separate brain pathways from object memory, and aphantasics would generally seem better at it.

No question but that human minds are varied.

My wife Marion and I discovered complementary experiences early in our relationship, but never pinpointed the underlying explanation. From the start, we knew that she’s much better with people’s names, and recall of events.

Whereas I could scarcely remember one line of poetry, she can recite not 10,000 lines, but 10,000 poems (only a slight exaggeration).

She enjoys novels, whereas I can’t arouse much enthusiasm (although maybe for Pride and Prejudice, which she supposes comes from Austen’s relative disregard for description).

We both enjoy movies – they don’t rely on visualisation. Mind you, I often get greater enjoyment than she does from movies based on her favourite novels – they are rarely quite as she imagined.

On the instruction “think of the colour red”, I get a fleeting impression, and move on. When I try to recall the smell of nutmeg, say, nothing happens. Marion has no such trouble.

Researchers referring to “visualisation, “imagination” and the “mind’s eye” betray a cultural priority for vision. Those with a vivid “mind’s eye” usually also have a strong “mind’s nose”, “mind’s ear”, “mind’s touch”, etc.

Reporting in 1880, the early researcher Francis Galton asked respondents to imagine “your breakfast-table as you sat down to it this morning – and consider carefully the picture that rises before your mind’s eye”. Some respondents saw the breakfast table “as well in all particulars as I can do if the reality is before me”. At the other end of the scale: “I recollect the breakfast table, but do not see it.” Galton did not report on other sensory recall, nor pleasures.

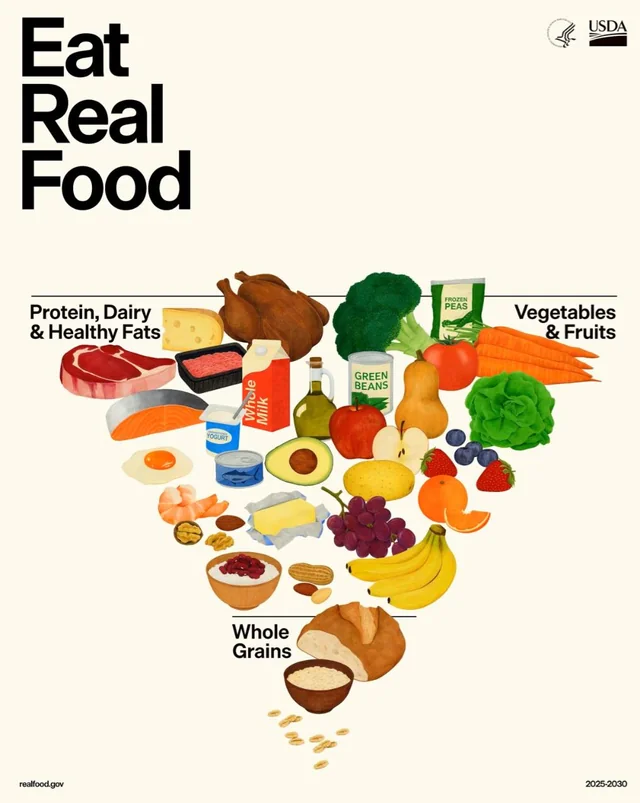

Delving into the absence of visual, auditory and other impressions raises questions about meals.

I’ve long been puzzled by the deluge of cookery pages. Why do we need yet another pavlova recipe? It turns out that where I might think “that’s a long list of ingredients”, Marion puts the ingredients together in her head, and decides if she’d enjoy eating the result.

Seemingly following my lack of olfactory recall, I have relative difficulty naming flavours, so that with wine, for instance, I struggle to find “vanilla notes”, “cedar” and “violets”. Instead of identifying particulars, I become immersed in compound sensations, starting with the wine’s “structure”.

That’s like meals as a whole. They are immediate. At a good meal, I am absorbed – engaged with the here-and-now of dishes, places, conversations and their connections. A good meal is complex, and hums. Existential.

Without intricate recall, I enjoy talking (yet again) about past stand-outs, and also look forward to the next experience. I always like to know something is planned.

I am now wondering about the act of writing. Just as some visual artists turn out not to visualise, but set images out in front of them, I love words on paper.

My books on cooking and economies contain numerous details, but these are meant to point to bigger concepts. Some readers might become preoccupied by descriptions, just as so-called “economists” might promote the simple mathematics of price, rather than absorb the full wonder of sharing the world.

Footnote: Research and writing on aphantasia has often been expressed in the negative – it is a “lack” or “disorder”. To quote a recent scientific paper, “visual imagery is absent or markedly impaired.” Even when protesting it’s not a disease, and citing examples of highly successful non-imagers, these same writers still focus on deficits. The very name aphantasia is pathologising.

That’s surprisingly easily turned around, so that one might say, for example, that many people – known as “phantasics” – suffer an overload of imagined sights, sounds, bodily states, and more.

George Herbert Betts reported on visual, auditory, gustatory, olfactory and other imagery in his 1909 study, and declared: “Very much of memory is accomplished without the use of imagery, and much of the imagery which accompanies memory is of no advantage to it.”

Questioning imagination’s importance for reading literature, he worried: “if a flood of profuse imagery should accompany the words as we read, interpretation and appreciation would be seriously interfered with.”

Without impediment, non-imagers engage with the factual and here-and-now, and think clearly.

Furthermore, aphantasia might be somewhat protective against PTSD, major depressive disorder, social phobia, and bipolar disorder (e.g., Cavedon-Taylor, 2022), given how these can be reinforced by visualising – flashbacks, or too vividly imagined dangers.

And yet, without leaping sheep, floating leaves or the sweet scent of vanilla, aphantasics might be exposed to other anxieties.

I am just beginning, and so is research generally.

For a sample:

Galton, Francis (1880), “Statistics of mental imagery”, Mind: A quarterly review, No. 19 (July 1880): 302-318

Betts, George Herbert (1909). Distribution and Functions of Mental Imagery (Columbia Univ. Contr. to Educ. No. 26.), New York: Teachers College, Columbia University

Cavedon-Taylor, Dan (2022), “Aphantasia and psychological disorder: Current connections, defining the imagery deficit and future directions,” Frontiers in Psychology, Published online 14 October 2022

Faw, Bill (2009), “Conflicting intuitions may be based on differing abilities: Evidence from

mental imaging research,” Journal of Consciousness Studies, 16(4), 45–68

Fox-Muraton, Mélissa (2021), “Aphantasia and the language of imagination: A Wittgensteinian exploration,” Analiza i Egzystencja 55 (2021)

Cavedon-Taylor, Dan (2022), “Aphantasia and psychological disorder: Current connections, defining the imagery deficit and future directions,” Frontiers in Psychology, Published online 14 October 2022

SOMETIMES THINGS fall into place so neatly as to be scarcely noticed. But I have never let myself forget the good fortune in discovering a simple savoury that we served to every customer from the first night of our restaurant in Tuscany in 1979 until Jennifer Hillier shut the doors on the Uraidla Aristologist seventeen years later.

SOMETIMES THINGS fall into place so neatly as to be scarcely noticed. But I have never let myself forget the good fortune in discovering a simple savoury that we served to every customer from the first night of our restaurant in Tuscany in 1979 until Jennifer Hillier shut the doors on the Uraidla Aristologist seventeen years later.

Returning to humour might distract from the creepiness. The secret agent comedy series Get Smart had a device called the “cone of silence” – those inside the bubble couldn’t hear; those outside could.

Returning to humour might distract from the creepiness. The secret agent comedy series Get Smart had a device called the “cone of silence” – those inside the bubble couldn’t hear; those outside could.