Duck press, Porcine, May 2025

I WAS FORTUNATE TO DINE OUT frequently for nearly six decades with journalist David Dale (27 March 1948-6 August 2025). This was often along with Suzie Anthony.

Our paths crossed early, when he was still a student and I was starting to make a name at the Sydney Morning Herald. He wrote me a long letter arguing that I didn’t understand guitarist Eric Clapton (or something like that).

I was the paper’s first or maybe second deliberate hire of a university graduate (my degree was in maths, and they had a “new maths” education supplement to bring out). When David and Suzie joined, they became “graduate cadets”, who were required to learn shorthand. I always reckoned he had the world’s most useless skill, shorthand slower than his long.

As young journalists at the Sydney Morning Herald, the three of us had lunch and dinner out many times a week for four or five years.

Later, in 1975, after a particularly beautiful lunch at Watson’s Bay, we three sat on a wall above the sand, and swore lifelong allegiance, which we honoured. We kept up meals together with a few unavoidable interruptions, such as living in different countries.

From my perspective, David seemed to lead a compartmentalised life. Early on, he had a girlfriend that Suzie and I never met. Mischievously, we knocked at his address, and were welcomed by a mother desperate to meet some of her boy’s friends, and she laid some of her concerns before us . Never met his father.

He also deliberately shied away from deep thoughts. When we met, he had completed Honours in Psychology, but was keener on Mad magazine, and turning to early Woody Allen movies.

David and my paths crossed more than once in Italy – and he never let me forget about revealing to both him and my father where to find the key to our ancient Tuscan watermill during one of Jennifer Hillier and my absences; David terrified my father in bed asleep, with Christopher demanding: “Do you know Bob Hope?” This was someone (the partner of colleague Julie Rigg’s expatriate mother) whom we all got to know well over there.

By then, he had joined the classy little gang putting out the radical media critic, the New Journalist (which I had co-founded with Leo Chapman and another old colleague who died this year, Paul Brennan).

Without hesitation, David became a third partner (along with Gabriel Gaté) in Duck Press that published my One Continuous Picnic in 1982. He leapt in as its editor.

In the late 1980s, I was invited to lunch in Adelaide, at his suggestion, by a visiting Bulletin journalist, Susan Williams, who grilled me about her editor. They married in Paris, without guests! When I married Marion Maddox in 1995, Suzie was my best person and David her assistant.

Towards the end, David increasingly talked streaming tv (that I never watch). Suzie and I found him reluctant for Friday lunches, but he was, we now imagine, in considerable pain. Our last get-together at La Riviera, he came with a walking frame.

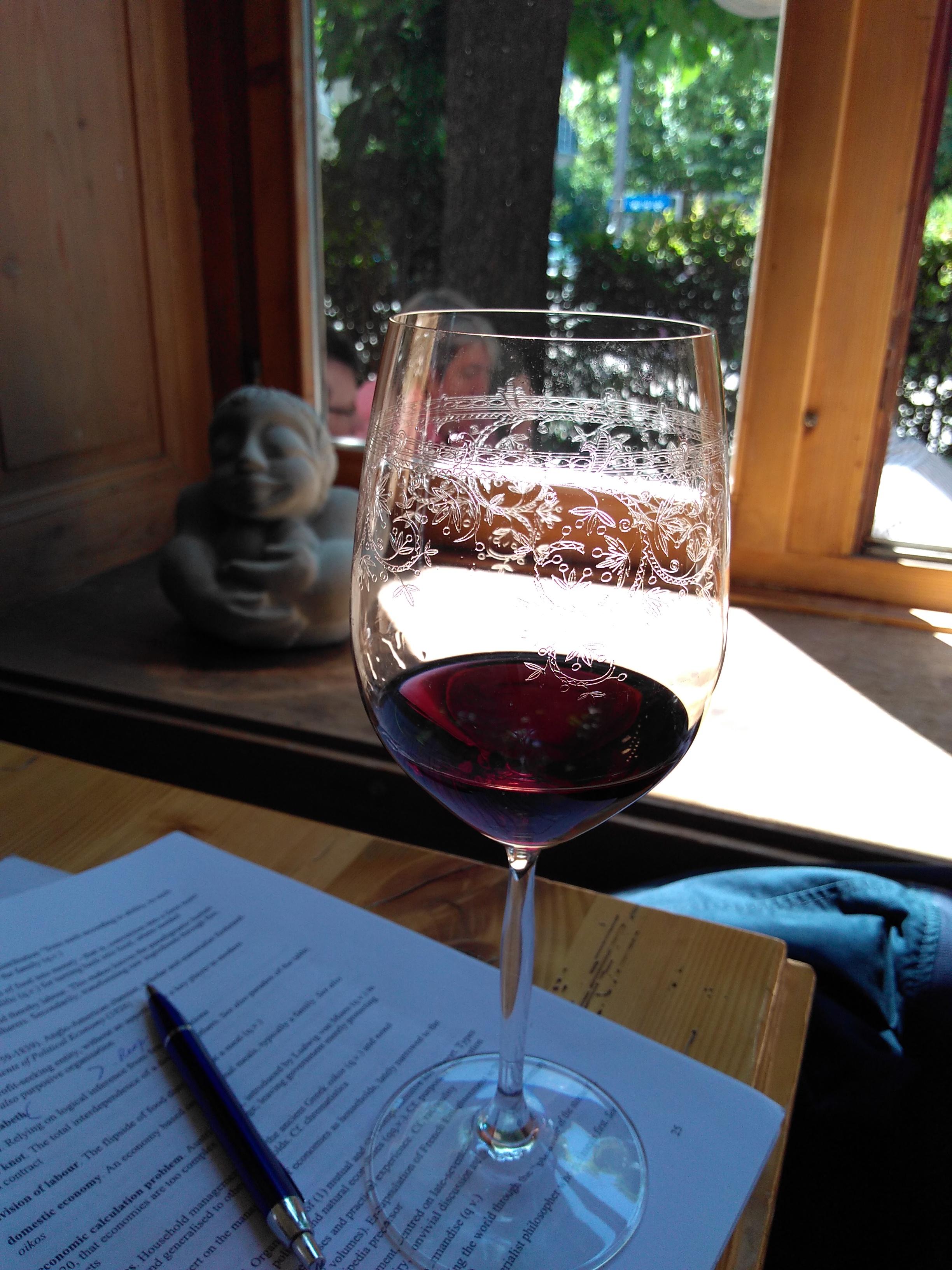

He’d enjoyed sauce from a duck press at Tour D’Argent (I think that was when he secretly got married). Not only the name of our publishing house, it remains my email address, but I hadn’t experienced a duck press.

Accordingly, for our little lunch group’s celebration of my 80th this year, we dined with a duck press at Porcine in Paddington. David needed a walking frame, and my wife a wheelchair; when we discovered the restaurant was up a flight of stairs; the chef generously offered to bring the paraphernalia down to a table set up in the wineshop below.

That was in May. It would be our final meal together. Our paths crossed a last time not many days ago. Marion had two recent stays at the Chris O’Brien Lifehouse. Only on the second, we learned David was in a nearby room all the time. Being a small world, Porcine chef Nik Hill’s wife Milly is a palliative care nurse there. (In an accumulating tragedy, Marion died on 16 September, back there again, two rooms from where David had been.)

When I popped in, he was true to himself, avoiding thoughts of imminent death. On another quick visit, I offered to bring some wine the next night. He was unable to drink, he said, on account of his nausea. He did admit, nevertheless, to wanting the best possible red to be his last mouthful.

That led me to recount how yet another friend with cancer had a few months ago quietly shared an aged burgundy that she happened to “just find in the cellar”. Fortunately, I thanked her profusely for a genuinely amazing experience. Only later, I discovered a bottle online for an equivalently amazing price. Definitely worth a last mouthful and, within days, our friend disappeared forever from our tables.

I hope David got his last taste.

Duck, Porcine. Photo: David Dale

PARIS IS ONE WORD worth more than a thousand pictures.

PARIS IS ONE WORD worth more than a thousand pictures.