AI fantasy of Trump toasting

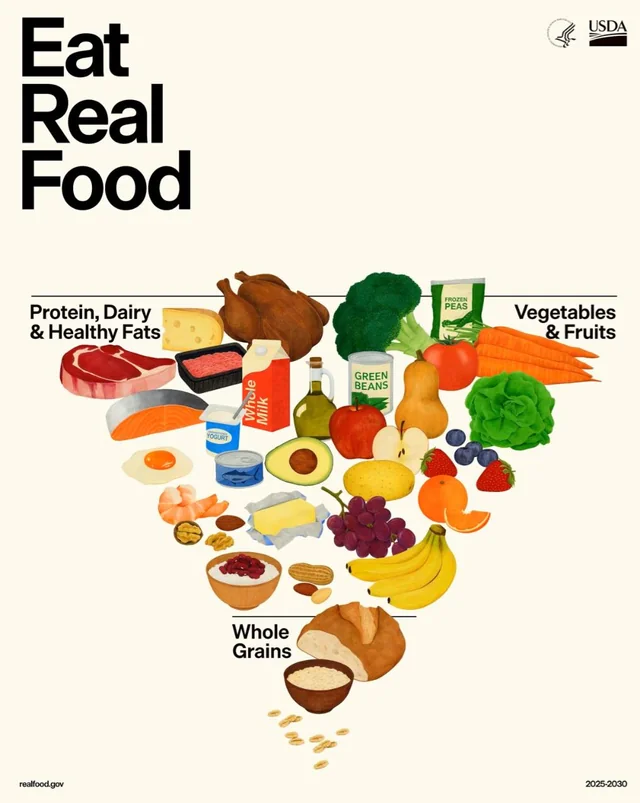

THE TRUMP Administration is “reclaiming the food pyramid” by turning the once familiar nutritional advice upside-down so as to laud meat and dairy. Whole grains and pulses are now squeezed into the sharp end balancing everything else precariously above.

The provocatively flipped dietary guidelines (7 January 2026) seek to dramatise the often fringe views of Trump’s Secretary of Health Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. Here, he gets the chance to encourage beef tallow, which McDonald’s abandoned in 1990 under health pressures (to the detriment of their fries).

The inverted hierarchy might snub mainstream nutrition but, in many way, the advice comes closer to foodie views. It’s hard to complain about the new instruction “The message is simple: eat real food.”

We can endorse a “dramatic reduction in highly processed foods laden with refined carbohydrates, added sugars, excess sodium, unhealthy fats, and chemical additives.” They also recommend: “Avoid sugar-sweetened beverages, such as sodas, fruit drinks, and energy drinks.”

Let’s not get carried away, because the guidelines continue to promote the idea of “good” and “bad” foods with next to no mention of social circumstances. The closest to advocacy of home cooking is the declaration: “Swap deep-fried cooking methods with baked, broiled, roasted, stir-fried, or grilled cooking methods.”

The advice has dropped any mention of alcohol’s involvement in cancer, because it’s “a social lubricant that brings people together”, medical influencer Dr Mehmet Oz explained at a White House briefing. He added that, while in “the best-case scenario, I don’t think you should drink alcohol,” it provides “an excuse to bond and socialize, and there’s probably nothing healthier than having a good time with friends in a safe way.”

Mind you, he might well be excusing after-hours drinks with the boys, rather than extolling the established health benefits of meals together.

Interestingly in this context, both Trump and Kennedy are teetotalers; Trump has never had a sip of alcohol – on the dying advice his older, alcoholic brother; and Kennedy finally sobered up after his arrest for heroin possession in 1983.

“Under President Trump’s leadership, we are restoring common sense, scientific integrity, and accountability to federal food and health policy,” the new guidelines boast. This hints at Trump’s original backing of Kennedy for campaigns that conspicuously repudiate “elites”.

Trump has delighted in offending experts. Yet just as Kennedy’s fringe medical views have often had some justification, even MAGA’s “deep state” conspiracy theories contain grains of truth. The reality here is the so-called state capture by moneyed interests. Corporations rule through armies of consultants and lobbyists, which has greatly compromised Democrat and other centre-left governments world-wide.

Free enterprise took over under the cover of “neoliberalism”, which let leftish leaders embrace racial, women’s, gay, scholarly, arts and other liberal causes. Unfortunately, the fundamental liberation was financial. With money unleashed globally, neoliberalism has given way to the ideology of winning.

Backed by formidable military power at home and abroad, Trump believes that the strong always win. He respects Putin and Netanyahu, but not wannabe strongman Maduro. Simply put, Trump is a fascist.

The imperial president is right about the strong winning, but the real response is strength in numbers. We need to restore John Locke’s plans for democratic republics, where the rule of law would displace the “state of war”. Locke envisaged physiological beings cooperating on mutual preservation through democratic economies. I have argued for this food-based radicalism in Meals Matter.

Locke’s arguments have been maligned and misapplied for three centuries. His common sense needs reinvigorating. Unlikely? To adapt Miley Cyrus, no pretending it’s not ending.